Our Lady of Guadalupe

| Our Lady of Guadalupe | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Tepeyac, Mexico City, Mexico |

| Date | 9 December 1531 |

| Witness | Saint Juan Diego |

| Type | Marian apparition |

| Holy See approval | 25 May 1754, pontificate of Pope Benedict XIV |

| Shrine | Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Tepeyac, Mexico. |

Our Lady of Guadalupe (Spanish: Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe (Spanish: Virgen de Guadalupe; Nahuatl: Tonantzin Guadalupe) is a celebrated Catholic image of the Virgin Mary.

According to tradition the image appeared miraculously on the cloak of Juan Diego, a simple indigenous peasant, on the hill of Tepeyac near Mexico City on December 12, 1531. Today it is displayed in the Basilica of Guadalupe nearby, the most visited Catholic shrine in the world.[1] The Virgin of Guadalupe is Mexico's most popular religious and cultural image, with the titles "Queen of Mexico",[2] "Empress of the Americas",[3] and "Patroness of the Americas";[4] Miguel Hidalgo in the Mexican War of Independence and Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution both carried Flags bearing the Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Guadalupe Victoria, the first Mexican president changed his name in her honour.

The iconography of the Virgin is impeccably Catholic: Miguel Sanchez, the author of the 1648 tract Imagen de la Virgen María, described her as the Woman of the Apocalypse from the New Testament's Revelation 12:1, "arrayed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars,"[5] and she is also described as a representation of the Immaculate Conception.[5] Yet despite this orthodoxy the image also contained a hidden layer of coded messages for the indigenous people of Mexico which goes a considerable way towards explaining her popularity.[6] Her blue-green mantle was the color reserved for the divine couple Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl;[7] her belt is interpreted as a sign of pregnancy; and a cross-shaped image symbolizing the cosmos and called nahui-ollin is inscribed beneath the image's sash.[8] She was called "mother of maguey,"[9] the source of the sacred beverage pulque,[10] "the milk of the Virgin",[11] and the rays of light surrounding her doubled as maguey spines.[9]

Contents |

The image

|

A series of articles on |

|---|

|

General articles |

|

Key Marian apparitions |

|

Expressions of devotion |

|

Specific articles |

Two accounts published in the 1640s, one in Spanish and the other in Nahuatl, tell how, during a walk from his home village to Mexico City early on the morning of December 9, 1531, (the Feast of the Immaculate Conception in the Spanish Empire),[12] the peasant Juan Diego saw a vision of a young girl of fifteen or sixteen, surrounded by light, on the slopes of the Hill of Tepeyac. Speaking in the local language, Nahuatl, the Lady asked for a church to be built at that site in her honor, and from her words Juan Diego recognized her as the Virgin Mary. Diego told his story to the Spanish bishop, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, who instructed him to return and ask the Lady for a miraculous sign to prove her claim. The Virgin told Juan Diego to gather some flowers from the top of Tepeyac Hill. It was winter and no flowers bloomed, but on the hilltop Diego found flowers of every sort, and the Virgin herself arranged them in his tilma, or peasant cloak. When Juan Diego opened the cloak before Zumárraga the flowers fell to the floor, and in their place was the Virgin of Guadalupe, miraculously imprinted on the fabric.[13]

History

Background

Following the Spanish Conquest in 1519-21 a temple of the mother-goddess Tonantzin at Tepeyac outside Mexico City was destroyed and a chapel dedicated to the Virgin built on the site. Newly converted Indians continued to come from afar to worship there. The object of their worship, however, was equivocal, as they continued to address the Virgin Mary as Tonantzin.[14]

The first record of the painting's existence is in 1556, when Archbishop Alonso de Montufar, a Dominican, preached a sermon commending popular devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe, a painting in the chapel at Tepeyac, where certain miracles had lately been performed. Days later he was answered by Francisco de Bustamante, head of the Colony's Franciscans and guardians of the chapel at Tepeyac, who delivered a sermon before the Viceroy expressing his concern that the Archbishop was promoting a superstitious regard for a painting by a native artist, Marcos Cipac de Aquino:

"The devotion that has been growing in a chapel dedicated to Our Lady, called of Guadalupe, in this city is greatly harmful for the natives, because it makes them believe that the image painted by Marcos the Indian is in any way miraculous."[15]

The next day Archbishop Montufar opened an enquiry. The Franciscans, holding that the image encouraged idolatry and supersition, testified that it was "painted yesteryear" by Marcos.[16] Appearing for the Dominicans, who favored allowing the Aztecs to worship the Guadalupe, was the Archbishop himself. The matter ended with the Franciscans deprived of custody of the shrine[17] and the tilma mounted and displayed within a much enlarged church.[18]

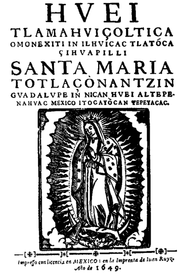

The first extended account of the image and the apparition comes in Imagen de la Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe, a guide to the cult for Spanish-speakers published in 1648 by Miguel Sanchez, a diocesan priest of Mexico City.[19] An anonymous Nahuatl language narrative, Huei tlamahuiçoltica ("The Great Event"), appeared at around the same time, probably written in 1649 by Luis Lasso de la Vega and based on Sánchez's narrative, which it closely mirrors. This contains Nican mopohua ("Here it is recounted"), a tract about the Virgin which contains the story of the apparition and the supernatural origin of the image, plus two other sections, Nican motecpana ("Here is an ordered account"), describing fourteen miracles connected with Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Nican tlantica ("Here ends"), an account of the Virgin in New Spain.[20]

Juan Diego

The growing fame of the image led to a parallel interest in Juan Diego. In 1666 the Church, with the aim of establishing a feast day in his name, began gathering information from people who had had known him, and in 1723 a formal investigation into his life was ordered, and much information was gathered. In 1987, under Pope John Paul II, who took an especial interest in saints and in non-European Catholics, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints declared him "venerable", and on May 6, 1990 he was beatified by the Pope himself during Mass at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, being declared “protector and advocate of the indigenous peoples," with December 9 as his feast day.

At this point historians and theologians began to question the quality of the evidence regarding Juan Diego. There is no mention of him or his miraculous vision in the writings of bishop Zumárraga, into whose hands he delivered the miraculous image, nor in the record of the ecclesiatic inquiry of 1556, which omits him entirely, nor anywhere else before the mid-17th century. Doubts as to his reality were not new: in 1883 Joaquín García Icazbalceta, historian and biographer of Zumárraga, in a confidential report on the Lady of Guadalupe for Bishop Labastida, was very hesitant to support the story of the apparition and stated his conclusion that there was never such a person.[21] Neither were they welcome: in 1897 the Bishop of Tamaulipas, Eduardo Sánchez Camacho, was forced to leave his post after expressing similar disbelief,[22] and as recently as 1996 the abbot of the Basilica of Guadalupe, Guillermo Schulenburg, was forced to resign following an interview with the Catholic magazine Ixthus, when he said that Juan Diego was "a symbol, not a reality."[23]

In 1995, with progress towards sanctification at a stand-still, Father Xavier Escalada, a Jesuit writing an encyclopedia of the Guadalupan legend, produced a deer skin codex, (Codex Escalada), illustrating the apparition and the life and death of Juan Diego. Although the very existence of this important document had been previously unknown, it bore the date 1548, placing it within the lifetime of those who had known Juan Diego, and bore the signatures of two trustworthy 16th century scholar-priests, Antonio Valeriano and Bernardino de Sahagún, thus verifying its contents.[24] Some scholars remained unconvinced, describing the discovery of the Codex as "rather like finding a picture of St. Paul's vision of Christ on the road to Damascus, drawn by St. Luke and signed by St. Peter",[5] but Diego was declared a saint, with the name of Saint Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, in 2002.

Scientific analysis

In 1979 Philip Serna Callahan investigated the composition of the image through infrared photography (used to detect sub-surface layers not visible to the naked eye).[25] He identified the moon, sun-rays and sash, stars and nahui olin, among other elements, as standard "International Gothic" additions, possibly from the second half of the 16th century.[26] The original image beneath these, namely the hands, face, blue mantle and rose-coloured robe, showed no underdrawing, sizing or overvarnish.[27]

In 1999 Leoncio Garza-Valdés of the University of Texas at San Antonio was engaged by the Archbishop of Mexico, Norberto Rivera Carrera, to undertaken a scientific study of the image using ultra-violet imaging.[16] Garza-Valdés' findings contradicted those by Callhan, finding three distinct layers involving all areas of the image, including those Callahan had identified as original. The oldest image, with striking similarities to the Spanish Lady of Guadalupe of Extremadura, shows a light-skinned Virgin carrying a child on her left arm. This layer bears the signature M.A. and the date 1556. A second Virgin has been painted over the first, and shows facial features of strong native American type. This second virgin was probably painted by Juan de Arrue around 1625.[16] The third image, the one currently visible, is painted 15 cm to the left of the second. Sample fibres given to Garza-Valdés proved to be of hemp and linen, not agave.[16]

The painting was examined again in 2002 by art restoration expert José Sol Rosales with stereo-microscopy (a technique used to identify pigments and the integrity of images). Rosales identified calcium sulfate, pine soot, white, blue, and green "tierras" (soil), reds made from carmine and other pigments, as well as gold, all consistent with 16th century materials and methods.[16] Despite Callahan's conclusion that the hands, face, mantle and robe could be identified as "original" and have never been painted, pigment has been applied to the highlight areas of the face sufficiently heavily as to obscure the texture of the underlying cloth, while the parting in the Virgin's hair is off-center, and her eyes, including the irises, have outlines, apparently applied by a brush; in addition there is obvious cracking and flaking of paint all along a vertical seam, and, in the robe's fold, what appear to be sketch lines, suggesting that the artist roughed out the figure before painting it.[28]

Cultural significance

Symbol of Mexico

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe is recognized as a symbol of all Catholic Mexicans. Miguel Sánchez, the author of the first Spanish language apparition account, identified Guadalupe as Revelation's Woman of the Apocalypse, and said:

"this New World has been won and conquered by the hand of the Virgin Mary...[who had] prepared, disposed, and contrived her exquisite likeness in this her Mexican land, which was conquered for such a glorious purpose, won that there should appear so Mexican an image."[5]

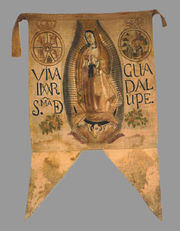

In 1810 Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla initiated the bid for Mexican independence with his Grito de Dolores, with the cry "Death to the Spaniards and long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!" When Hidalgo's mestizo-indigenous army attacked Guanajuato and Valladolid, they placed "the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which was the insignia of their enterprise, on sticks or on reeds painted different colors" and "they all wore a print of the Virgin on their hats."[29] After Hidalgo's death leadership of the revolution fell to a zambo/mestizo priest named Jose Maria Morelos, who led insurgent troops in the Mexican south. Morelos adopted the Virgin as the seal of his Congress of Chilpancingo, inscribing her feast day into the Chilpancingo constitution and declaring that Guadalupe was the power behind his victories:

"New Spain puts less faith in its own efforts than in the power of God and the intercession of its Blessed Mother, who appeared within the precincts of Tepeyac as the miraculous image of Guadalupe that had come to comfort us, defend us, visibly be our protection."[29]

Simón Bolívar noticed the Guadalupan theme in these uprisings, and shortly before Morelos' death in 1815 wrote: "...the leaders of the independence struggle have put fanaticism to use by proclaiming the famous Virgin of Guadalupe as the queen of the patriots, praying to her in times of hardship and displaying her on their flags...the veneration for this image in Mexico far exceeds the greatest reverence that the shrewdest prophet might inspire."[5] One of Morelos' officers, Felix Fernandez, would later become the first Mexican president, even changing his name to Guadalupe Victoria.[29]

In 1914, Emiliano Zapata's peasant army rose out of the south against the government of Porfirio Diaz. Though Zapata's rebel forces were primarily interested in land reform—"tierra y libertad" (land and liberty) was the slogan of the uprising—when his peasant troops penetrated Mexico City they carried Guadalupan banners.[30] More recently, the contemporary Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) named their "mobile city" in honor of the Virgin: it is called Guadalupe Tepeyac. EZLN spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos wrote a humorous letter in 1995 describing the EZLN bickering over what to do with a Guadalupe statue they had received as a gift.[31]

Mestizo culture

"The Aztecs…had an elaborate, coherent symbolic system for making sense of their lives. When this was destroyed by the Spaniards, something new was needed to fill the void and make sense of New Spain…the image of Guadalupe served that purpose."[32]

Hernan Cortez, the Conquisador who overthrew the Aztec empire in 1521, was a native of Extremadura, home to Our Lady of Guadalupe. By the 1500s the Extremadura Guadalupe, a statue of the Virgin carved by Saint Luke the Evangelist, was already a national icon. It was found at the beginning of the 14th century when the Virgin appeared to a humble shepherd and ordered him to dig at the site of the apparition. The recovered Virgin then miraculously helped to expel the Moors from Spain, and her small shrine evolved into the great Guadalupe monastery. One of the more remarkable attributes of the Guadalupe of Extremadura is that she is dark, like the Americans, and thus she became the perfect icon for the missionaries who followed Cortez to convert the natives to Christianity.[18]

According to the traditional account, the name of Guadalupe was chosen by the Virgin herself when she appeared on the hill outside Mexico City in 1531, ten years after the Conquest.[33] According to secular history, Bishop Alonso de Montúfar, in the year 1555, commissioned a Virgin of Guadalupe from a native artist, who gave her the dark skin which his own people shared with the famous Extremadura Virgin.[18] Whatever the connection between the Mexican and her older Spanish namesake, the fused iconography of the Virgin and the indigenous Mexican goddess Tonantzin provided a way for 16th century Spaniards to gain converts among the indigenous population, while simultaneously allowing 16th century Mexicans to continue the practice of their native religion.[34]

Guadalupe continues to be a mixture of the cultures which blended to form Mexico, both racially and religiously,[35] "the first mestiza",[36] or "the first Mexican".[37] "bringing together people of distinct cultural heritages, while at the same time affirming their distinctness."[38] As Jacques Lafaye wrote in Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe, "...as the Christians built their first churches with the rubble and the columns of the ancient pagan temples, so they often borrowed pagan customs for their own cult purposes."[39] The author Judy King asserts that Guadalupe is a "common denominator" uniting Mexicans. Writing that Mexico is composed of a vast patchwork of differences—linguistic, ethnic, and class-based—King says "The Virgin of Guadalupe is the rubber band that binds this disparate nation into a whole."[37] The Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes once said that "... you cannot truly be considered a Mexican unless you believe in the Virgin of Guadalupe."[40] Nobel Literature laureate Octavio Paz wrote in 1974 that "the Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery".[41]

Catholic Church

Beliefs and miracles

Catholic sources describe the many miraculous and supernatural properties of the image. In 1629 she saved Mexico City from a great flood, and in 1737 saved the people from plague that claimed the lives of 700,000.[42] The tilma has maintained its structural integrity over nearly 500 years, while replicas normally last only about 15 years before suffering degradation;[43] it repaired itself with no external help after a 1791 ammonia spill that did considerable damage, and in 1926 an anarchist bomb destroyed the altar, but left the icon unharmed.[44]

In 1929 and 1951 photographers found a figure reflected in the Virgin's eyes; upon inspection they said that the reflection was tripled in what is called the Purkinje effect, commonly found in human eyes.[45] An ophthalmologist, Dr. Jose Aste Tonsmann, later enlarged an image of the Virgin's eyes by 2500x and found not only the aforementioned single figure, but images of all the witnesses present when the tilma was first revealed before Zumaragga in 1531, plus a small family group of mother, father, and a group of children, in the center of the Virgin's eyes, fourteen persons in all.[46]

Numerous Catholic websites repeat an unsourced claim[44] that in 1936 biochemist Richard Kuhn analyzed a sample of the fabric and announced that the pigments used were from no known source, whether animal, mineral or vegetable.[46] Dr. Philip Serna Callahan, who photographed the icon under infrared light, discovered from his photographs that portions of the face, hands, robe, and mantle had been painted in one step, with no sketches or corrections and no visible brush strokes.[47]

Pontifical pronouncements

With the Brief Non est equidem of May 25, 1754, Pope Benedict XIV declared Our Lady of Guadalupe patron of what was then called New Spain, corresponding to Spanish Central and Northern America, and approved liturgical texts for the Holy Mass and the Breviary in her honor. Pope Leo XIII granted new texts in 1891 and authorized coronation of the image in 1895. Pope Pius X proclaimed her patron of Latin America in 1910. Pope Pius XII declared the Virgin of Guadalupe "Queen of Mexico and Empress of the Americas" in 1945, and "Patroness of the Americas" in 1946. Pope John XXIII invoked her as "Mother of the Americas" in 1961, referring to her as Mother and Teacher of the Faith of All American populations, and in 1966 Pope Paul VI sent a Golden Rose to the shrine.[48]

Pope John Paul II visited the shrine in the course of his first journey outside Italy as Pope from 26 to January 31, 1979, and again when he beatified Juan Diego there on May 6, 1990. In 1992 he dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe a chapel within St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican. At the request of the Special Assembly for the Americas of the Synod of Bishops, he named Our Lady of Guadalupe patron of the Americas on January 22, 1999 (with the result that her liturgical celebration had, throughout the Americas, the rank of solemnity), and visited the shrine again on the following day. On July 31, 2002, the Pope canonized Juan Diego before a crowd of 12 million, and later that year included in the General Calendar of the Roman Rite, as optional memorials, the liturgical celebrations of Saint Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (December 9) and Our Lady of Guadalupe (December 12).[48]

Devotions

The shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe is the most visited Catholic pilgrimage destination in the world. Over the Friday and Saturday of 11 to 12 December 2009, a record number of 6.1 million pilgrims visited the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico to commemorate the anniversary of the apparition.[49]

The Virgin of Guadalupe is considered the Patroness of Mexico and the Continental Americas; she is also venerated by Native Americans, on the account of the devotion calling for the conversion of the Americas. Replicas of the tilma can be found in thousands of churches throughout the world, and numerous parishes bear her name.

Our Lady Guadalupe was considered the secondary[50] "Patroness of the Philippines" from 1935 until 1942, and her feast day is still celebrated in the archipelago. The icon there is especially invoked by people working against the passage of the Reproductive Health Bill.

Buildings for devotion

- The Basilica of Guadalupe, the shrine founded on the original site on Tepayac Hill in Mexico City

- The Basílica of Guadalupe in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico

- The Cathedral of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Zamora, Michoacán

- The Cathedral Santuario de Guadalupe in Dallas, Texas.

- The Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in La Crosse, Wisconsin

- The National Shrine of Our Lady Of Guadalupe in Makati City, Philippines

- Our Lady of Guadalupe Shrine, Des Plaines, Illinois.

Notes

- ↑ EWTN.com

- ↑ Marys-Touch.com

- ↑ CatholicFreeShipping.com

- ↑ Britannica.com

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Brading, D.A. Mexican Phoenix. Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition Across Five Centuries. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001.

- ↑ Elizondo, Virgil. Guadalupe, Mother of a New Creation. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1997

- ↑ UTPA.edu, "La Virgen de Guadalupe", accessed 30 November 2006

- ↑ Tonantzin Guadalupe, by Joaquín Flores Segura, Editorial Progreso, 1997, ISBN 9706411453, 9789706411457, p. 66-77

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Taylor, William B. (1979). Drinking, Homicide, and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages. Stanford: Stanford University Press

- ↑ Del Maguey, Single Village Mezcal. "What if Pulque?". http://www.mezcal.com/pulque.html. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ↑ Bushnell, John (1958). "La Virgen de Guadalupe as Surrogate Mother in San Juan Aztingo". American Anthropologist 60 (2): 261

- ↑

G. Lee (1913). "Shrine of Guadalupe". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

G. Lee (1913). "Shrine of Guadalupe". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ English translation of the account in Nahuatl

- ↑ D. A. Brading, "Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe" (Cambridge University Press, 2001) pp.1-2

- ↑ Poole, Stafford. Our Lady of Guadalupe. The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531-1797. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1997.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Vera, Rodrigo. Sectas.org, "La Guadalupana, tres imagenes en uno" Proceso, May 25, 2002, accessed 29 November 2006

- ↑ The Wonder of Guadalupe, Francis Johnston, TAN Books, 1981, p. 47

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Dunning, Brian. "The Virgin of Guadalupe." Skeptoid Podcast. Skeptoid Media, Inc., 13 Apr 2010. Web. 12 Jul 2010.

- ↑ D. A. Brading, "Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe" (Cambridge University Press, 2001) p.5

- ↑ Sousa, Lisa; Stafford Poole, and James Lockhart (trans. and trans.) (1998). The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de la Vega's Huei tlamahuiçoltica of 1649. UCLA Latin American studies, vol. 84; Nahuatl studies series, no. 5. Stanford & Los Angeles, California: Stanford University Press, UCLA Latin American Center Publications. ISBN 0-8047-3482-8. OCLC 39455844 pp.42–47)

- ↑ Juan Diego y las Apariciones el pimo Tepeyac (Paperback) by Joaquín García Icazbalceta ISBN 9709277138

- ↑ "Divided by an Apparition." New York Times. September 5, 1896; p. 3. De la Torre Villar, Ernesto, y Navarro de Anda, Ramiro. "Testimonios Históricos Guadalupanos." Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982

- ↑ Daily Catholic. December 7, 1999, accessed November 30, 2006

- ↑ Peralta, Alberto (2003). "El Códice 1548: Crítica a una supuesta fuente Guadalupana del Siglo XVI". Artículos. Proyecto Guadalupe. http://www.proyectoguadalupe.com/apl_1548.html. Retrieved 2006-12-01.(Spanish), Poole, Stafford (July 2005). "History vs. Juan Diego". The Americas 62: 1–16. doi:10.1353/tam.2005.0133., Poole, Stafford (2006). The Guadalupan Controversies in Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5252-7. OCLC 64427328.

- ↑ Brief overview of IR photography and art restoration at essentialvermeer.com

- ↑ Miguel Leatham (2001). "Indigenista Hermeneutics and the Historical Meaning of Our Lady of Guadalupe of Mexico". Folklore Forum. Google Docs. p. 34-5. http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:dEgEmetVFmAJ:https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/2068/22%281,2%29%252027-39.pdf%3Bjsessionid%3D1227C6A7E3165C653E62BC087491548F%3Fsequence%3D1+Indigenista+Hermeneutics+and+the+Historical+Meaning+of+Our+Lady+of+Guadalupe+of+Mexico+Miguel+Leatham&hl=en&gl=au&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEEShBuwpsPCrRFNOB1CPn0IkariSUleG-UbiXbKllTESfpx7frasl4kJ_RfQmq_jLZqHwBQZeY9D18iVXQFC4GGejIFTKQDdUL_xKDWInaVC2Xnzuba84CEduSHziBn5T02jJbL2c&sig=AHIEtbRf05-RnI24o_h8Uwq5zShqIrFGnw.

- ↑ Jeanette Rodríguez. "Our Lady of Guadalupe: faith and empowerment among Mexican-American women". Google Docs. p. 22. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=n_sIz_cv4fYC&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=Dr.+Philip+Callahan+guadalupe&source=bl&ots=7_CXThhkor&sig=XpOihWnrxxksdSW2pE6zNkdgsRk&hl=en&ei=V4pPTLmnJor80wTI66yfBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9&ved=0CDQQ6AEwCDgK#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Joe Nickell, "Camera Clues: A Handbook for Photographic Investigation" (University Press of Kentucky, 2004) p.189

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Krauze, Enrique. Mexico, Biography of Power. A History of Modern Mexico 1810-1996. HarperCollins: New York, 1997.

- ↑ Documentary footage of Zapata and Pancho Villa's armies entering Mexico City can be seen at YouTube.com, Zapata's men can be seen carrying the flag of the Guadalupana about 38 seconds in.

- ↑ Subcomandante Marcos, Flag.blackened.net, "Zapatistas Guadalupanos and the Virgin of Guadalupe" 24 March 1995 , accessed 11 December 2006.

- ↑ Harrington, Patricia. "Mother of Death, Mother of Rebirth: The Virgin of Guadalupe." Journal of the American Academy of Religion. Vol. 56, Issue 1, p. 25-50. 1988

- ↑ Sancta.org, "Why the name 'of Guadalupe'?", accessed 30 November 2006

- ↑ The Virgin of Guadalupe, Is the Virgin of Guadalupe a miraculous apparition, a dismissable religious icon, or does it have more importance? (@ skeptoid.com, accessed June 2010)

- ↑ Elizondo, Virgil. AmericanCatholic.org, "Our Lady of Guadalupe. A Guide for the New Millennium" St. Anthony Messenger Magazine Online. December 1999. , accessed 3 December 2006.

- ↑ Lopez, Lydia. "'Undocumented Virgin.' Guadalupe Narrative Crosses Borders for New Understanding." Episcopal News Service. December 10, 2004.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 King, Judy. MexConnect.com , "La Virgen de Guadalupe—Mother of All Mexico" Accessed 29 November 2006

- ↑ O'Connor, Mary. "The Virgin of Guadalupe and the Economics of Symbolic Behavior." The Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. Vol. 28, Issue 2. p. 105-119. 1989.

- ↑ Lafaye, Jacques. Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe. The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1976

- ↑ Demarest, Donald. "Guadalupe Cult...In the Lives of Mexicans." p. 114 in A Handbook on Guadalupe, Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate, eds. Waite Park MN: Park Press Inc, 1996

- ↑ Paz, Octavio. Introduction to Jacques Lafaye's Quetzalcalcoatl and Guadalupe. The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness 1531-1813. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976

- ↑ maryourmother.net

- ↑ Guerra, Giulio Dante. AlleanzaCattolica.org, "La Madonna di Guadalupe". 'Inculturazione' Miracolosa. Christianita. n. 205-206, 1992. , accessed 1 December 2006

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Experiencefestival.com

- ↑ Web.archive.org. "The Eyes" Interlupe. Accessed 3 December

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Science Sees What Mary Saw From Juan Diego’s Tilma", catholiceducation.org

- ↑ Sennott, Br. Thomas Mary. MotherOfAllPeoples.com , "The Tilma of Guadalupe: A Scientific Analysis".

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Notitiae, bulletin of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, 2002, pages 194-195

- ↑ Znit.org

- ↑ CBConline.org, "Our Lady of Guadalupe parish church now an Archdiocesan Shrine"

References

Books

- Xavier Escalada. "Enciclopedia Guadalupana", México D.F.

- Mariano Cuevas, S.J. "Album Histórico Guadalupano del IV Centenario", 1930. México D.F.

- León-Portilla, Miguel. "Tonanzin Guadalupe", Fondo de Cultura Económica 2000, México D.F.

- Robert J. Fox. A Handbook on Guadalupe, Fatima Family Apostolate, 1988, USA

Websites

- Goeringer, Conrad. "Virgin of Guadalupe a Fraud, Says Abbot." PositiveAtheism.org, accessed July 9, 2007

- Conchiglia. "Movimento d'Amore San Juan Diego dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe", October 24, 2001. Conchiglia.ch accessed March 6, 2007

- Garduño, Thalia Ehrlich. "Virgen de Tlaltenango." Mariologia.org , accessed November 29, 200

- LaVirgenMaria.ex, "La Virgen Maria".

- Our Lady of Guadalupe." catholic.org Catholic.org, accessed November 30, 2006

- Our Lady of Guadalupe." MaryOurMother.net

- "Our Lady of Guadalupe." livingmiracles.net LivingMiracles.net, accessed November 30, 2006

- "Our Lady of Guadalupe. Historical sources." L'Osservatore Romano. January 23, 2002, page 8. EWTN.com

- Zwick, Mark and Louise. "Why San Juan Diego, a Saint for Nobodies, Means So Much to the Houston Catholic Worker." Houston Catholic Worker newspaper, September-October 2002 CJD.org

- The Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, The Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe Des Plaines, Illinois, MadreDeAmerica.org

Periodicals

- Peterson, Jeannette Favot. "The Virgin of Guadalupe. Symbol of Conquest or Liberation?" Art Journal. Vol. 51, Issue 4, p. 39. 1992

External links

- Caryana.org, The Story of Our Lady of Guadalupe

- CatholicIntl.com, New Discoveries of the Constellations on the Tilma of Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Udayton.edu, Marian library's discussion of Guadalupe as Mexican national symbol

- NEWS.BBC.co.uk, BBC photo essay of 12 December festivities in San Miguel de Allende, Gto.

- Pbase.com, Photo essay on Los Angeles Latino community's Guadalupan murals, altars and statues.

- NewAdvent.org, The Catholic Encyclopedia

- Sancta.org, A Catholic site dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe

- (Spanish) ProyectoGuadalupe.com, Critical essays, iconography and documentary information about the Guadalupe

- (Spanish) Biblioteca.itam.mx, Mínima Bilbliografía el Guadalupanismo